Today in Tedium: Selling a new idea is hard, especially when the audience potentially may not understand it. There may be interest in trying it out, but only if the commitment is minimal—upon the first sign of danger, they want to be able to hit the exit sign. For the past two decades, this has been the real promise of the Linux live CD: Put this disc (or USB drive) inside of your computer, try it out, see how it goes. If you really like it, install it. But what you might not realize was how we got this now-quite-common format, and that part of its selling point was its physical component. And it was a bigger selling point than you might guess. Today’s Tedium talks about the unusual shape of the early era of the Linux live CD. — Ernie @ Tedium

Today’s Tedium is sponsored by Masterworks. More from them in a second.

“Bear in mind that this is an alpha release. If you experience problems, be prepared to do a certain amount of detective work to try to narrow the problem down to certain hardware or software components. If you can debug and fix the problem, that’s even better.”

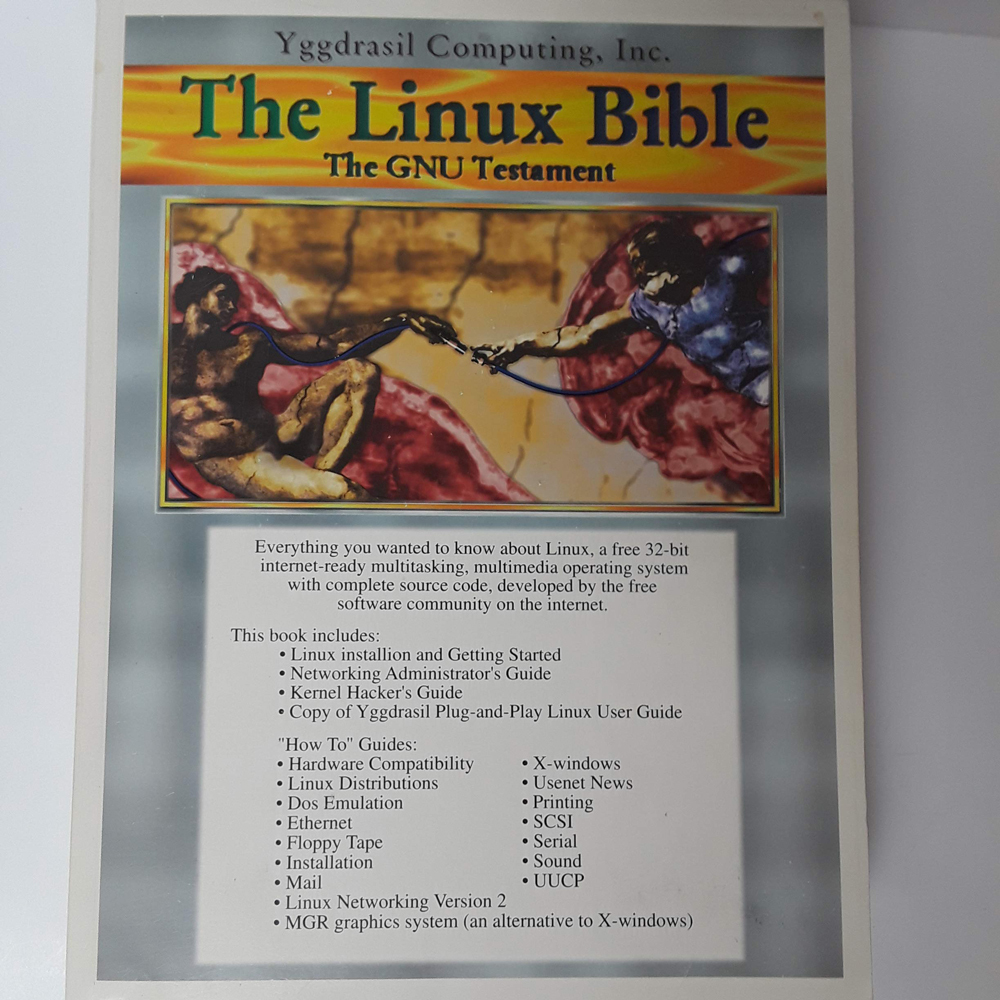

— Adam J. Richter, an early Linux developer, describing his work on what could be referred to as the first Linux Live CD, Yggdrasil Linux/GNU/X. The CD, built just a year after Linus Torvalds started work on the Linux kernel and developed for x86-class PCs, cost $99 at launch, but was offered with a 30-day money-back guarantee for those who couldn’t get it to work. At the time, CD-ROMs spun at slower speeds with data transfer rates of below 1 megabyte, which made the CD-ROM less useful than it might have been in later iterations.

The Linux Bible, an early distribution effort by Yggdrasil Computing. (via Amazon)

Why—and how—the Linux live CD found its unusally shaped groove

If you want to use Linux in the modern day, your options are relatively easy: Download an ISO or (especially in the case of a single-board computer like a Raspberry Pi) put a disk image on a MicroSD card. Easy peasy—just go to DistroWatch and get started.

But in the 1990s, as Linux was first emerging as a potential operating system with mainstream appeal, the options weren’t necessarily so easy to grasp, which meant that you had to put it on a disk drive before you could actually use it. But doing so in a way that wasn’t destructive went over the heads of new users.

And given that Windows already gave users enough heartache, if Linux was going to win over a large audience, it was going to have to be presented in a way that a regular person could try without the risk of breaking anything.

There was just one problem: The technology wasn’t yet ready. The original alpha of Yggdrasil Linux/GNU/X, considered the first Live CD built expressly for Linux, released well before the term “Live CD” was even in use, required 8 megabytes of RAM, at a time when that much RAM was not necessarily common in mainstream computers. (The final release, still downloadable today, lowered the number to 4MB of RAM.)

While a landmark of sorts today, Yggdrasil quickly faded from view, and that meant that others would be left to try again.

The passage of time was a useful thing, however. In 2000, the Pentium III was common, and the Pentium 4 had just been released. The CD-ROM drive, long having gotten past the caddy, had reached speeds of as high as 52X, whirring along at more than 6,000 revolutions per minute, to draw read speeds above 6 megabytes per second. (By comparison, the average SATA SSD maxes out at 600 megabytes per second; a modern high-end hard drive can hit maybe a third of that speed.) And DVD-ROMs, which started at 1.25 megabytes per second in speed (nearly 10 times that of a 1X CD-ROMs) were becoming mainstream by this point, and could hold significantly more data, to boot.

But then, there was the portability factor—how were we going to get these live CDs out to lots of people? If you ever went to a Barnes & Noble and picked up a Linux magazine off the rack, you know the answer already—the live CD distros that were often distributed with magazines! But that didn’t necessarily make itself clear at first.

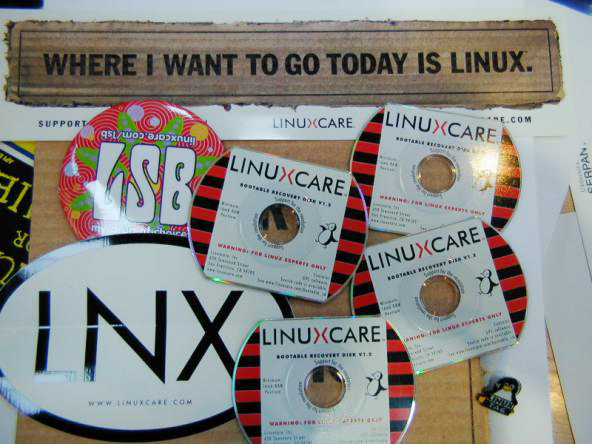

The Linuxcare business card distro proved a big hit at tradeshows. (via Slashdot)

Enter the bootable business card.

As I’ve written in the past, the format of the CD-ROM did not need to necessarily be in a 4.75-inch round disc form. As long as it spun around the spindle and could be picked up by a laser, it was perfectly usable. This opened up opportunities for CD-ROMs of different sizes. For example, the mini-CD, which could be as small as 80 millimeters in size and hold up to 24 minutes of music or 210 megabytes of data. This format, most popular in Japan, was often used for CD singles, effectively in the same way that vinyl singles were.

And one of the ways that it appeared was in business card form. Back in 2017, I called this format “tacky” and so obviously bad that even Scott Adams was compelled to make fun of it, which was perhaps unfair, but let’s face it, if you’re distributing a business card using a CD-ROM, you’re probably asking too much of your audience.

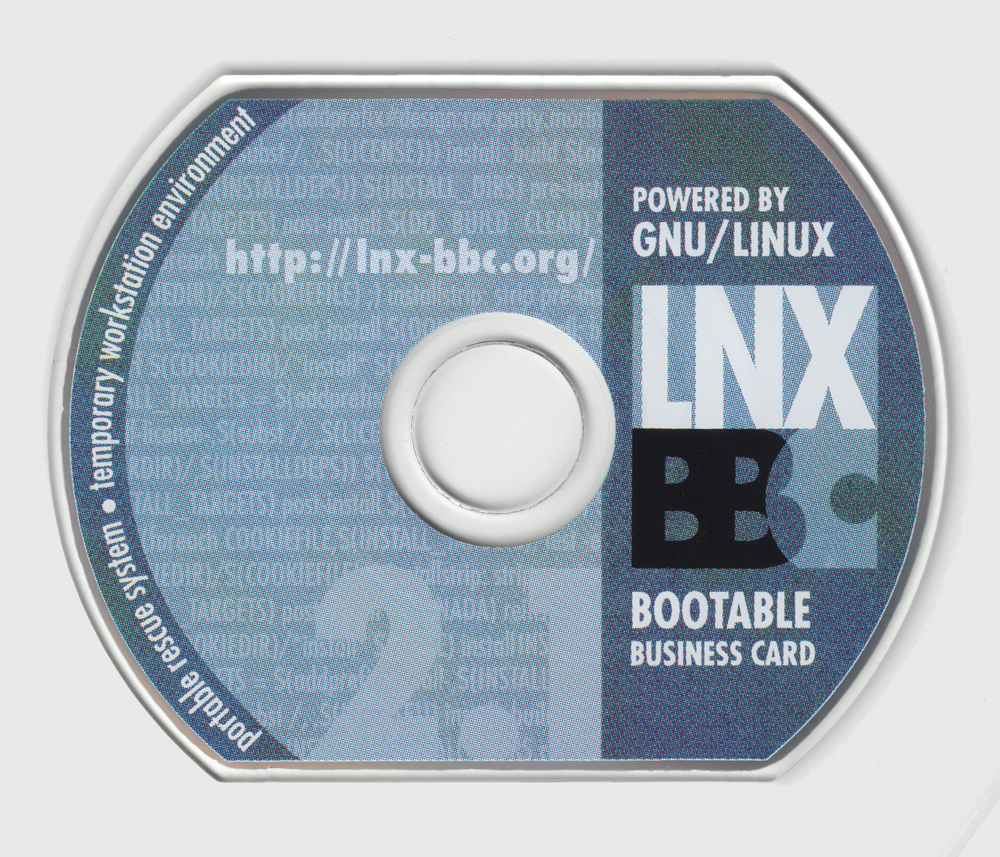

LNX-BBC, an early example of a Linux live CD. (via Internet Archive)

But one thing I didn’t discuss back then was that this unusually tacky format had a direct influence on the evolution of the Linux live CD, as people who began pushing this format forward were directly inspired by this wallet-sized disclet.

In 1999, a group of employees for the company Linuxcare came upon the idea to create a distro small enough that it could be distributed to people on this tiny disc. As the Linuxcare website explained back in the day:

The Bootable Business Card is a complete miniature Linux system on a bootable CD-ROM disc in the size and shape of a business card. It is a bootable mini-CD which should work in almost any PC-compatible machine capable of booting CD-ROMs. Boot our Bootable Business Card and you have 108MB of usable software at your fingertips. It contains a full complement of recovery and rescue software. On the booted system are over 500 diagnostic programs, utilities, and networking clients.

Carry it in your pocket, and immediately have the means to boot any PC as a networked Linux workstation, examine and repair a damaged system, diagnose network problems, make backups, mirror hard drives … you can have unmatched flexibility and power in a variety of unexpected situations.

They quickly proved huge hits with more technical users, notes Linux.com contributor Russell C. Pavlicek in a 2000 article.

“These CDs quickly became the talk of the Linux trade show circuit, and the earliest editions of the CD were among the most sought after giveaways at LinuxWorld and the Atlanta Linux Showcase,” he said.

It was the rare form of swag that was actually incredibly useful and could be used at the day job. (Apologies to canvas tote bags.) And it expanded interest in the general concept of live CDs, which could carry deep utility uses along with the more common modern day use case of just trying out a new operating system.

The LNX-BBC boot interface, in XWindows mode, running through the QEMU emulator on my M1 Mac. Alas, no mouse support. Nonetheless, not bad for a program only 50 megs in size.

In just a couple years, more business-card-sized Linux distros would appear, including direct descendant LNX-BBC, which can be checked out via the Internet Archive. Soon after that, every major Linux distribution would begin to be distributed on CD-ROMs and DVD-ROMs in a “live CD” format, one further encouraged by the growth of the flash drive, which made testing new systems painless.

Now trying out a new distro is often as easy as a single download. In fact, the large amount of choice is actually seen as the hurdle now—not the ease of access.

Jeff Bezos, Eric Schmidt, and Bill Gates LOVE This Secret Asset Class

These tech billionaires are pouring millions into an exclusive asset class that has generated attractive returns for decades—but you would never know it by looking at their portfolios. What do they invest in that you don’t? Blue-chip art: an exclusive asset class that is expected to grow from $1.7 to $2.6 trillion by 2026.

The only problem? Unless you have a cool $10,000,000 laying around you can’t be a part of this billionaires boys club. Right? Think again. Introducing Masterworks, my favorite platform for investing in proven artists like Basquiat, Warhol, and Banksy. Contemporary art prices outperformed the S&P 500 by 174% from 1995-2020, so it’s no surprise 84% of ultra-high-net-worth individuals collect art.

If you’re looking for a solid and nearly uncorrelated asset to add to your portfolio, I recommend checking out Masterworks.

Bonus: I’ve partnered with Masterworks to let Tedium subscribers skip their 25,000 person waitlist, so do yourself a favor and sign up today.*

* See important info.

“How does this sound? We start with a no-commitment Linux that comes complete with a full KDE graphical desktop, networking tools (including Netscape), games, tools and a plethora of additional programs. Best of all, this Linux distribution runs directly from the CD-ROM. That’s right: you can leave your hard disk completely untouched and still try Linux. Interested?”

— Marcel Gagné, a writer for LinuxJournal circa 2000 in a column about “Linux for the Timid” that helped to make the case for DemoLinux, one of the earliest live-CD distributions that was intended for regular users. This disc essentially made it possible for regular users to try out Linux without having to worry about anything crazy like installing stuff on their hard drive or partitioning their disc to make it happen. While no longer active, it helped set the stage for similar ongoing Linux distributions, like Finnix, and more mainstream live distributions like Debian, Fedora, and Ubuntu soon followed suit.

(via Thirty Three Forty)

The modern day Linux business card is a bootable PCB complete with its own chip

As I pointed out above, Linux and business cards have a surprisingly cozy relationship, one that seems to have extended beyond simple fascination.

A case in point on the matter involves the work of George Hilliard, an embedded systems engineer who highlighted just how good he is at embedded systems by designing a business card that could plug into a USB port and run a Linux shell that a user could use to access a few programs, including games.

“I designed and built everything myself. This is literally my job, and I enjoy it, so much of the challenge was finding parts that were cheap enough for a hobbyist,” he wrote on his blog back in 2019.

It is an amazing card that manages to fit in an actual processor, RAM, and 8 megabytes of flash storage (in the latter case, the flash was such a small size that it took a while to load due to the need to use. And given the fact that he had to put in all the components himself, it’s impressive that the final result was as inexpensive as it was—other than time and shipping, the result cost him just $2.88 per card to build.

Of course it wasn’t necessarily easy—there were issues with the PCB being too small for a traditional USB port, and trying to get the device to properly boot was a challenge because of a bug in the U-Boot’s implementation with the flash drive, he writes—but the result is something that shows just how versatile Linux really is. Two decades ago, putting a full Linux software implementation on something that could fit into your wallet was a big deal and arguably revolutionized Linux in ways we’re still seeing the effects of.

Now, it can be done with both Linux software and hardware. It may be the smallest way that Linux highlights the power of many.

Recently, I’ve been testing out the PinePhone, which is a fascinating device because it really highlights the work-in-progress nature of Linux on the smartphone. A lot of really great ideas, some of which started in commercial settings, that are slowly coalescing into something that a normal person might want to use at some point. The PinePhone, on its own, isn’t there—but you can see the starting point of an ecosystem that will eventually get there.

In a lot of ways, mainstream Linux is there—heck, it showed up in a mainstream movie recently—and one has to imagine that the way it found its path to the regular person was through the live CD.

The PinePhone’s equivalent to that is the microSD card slot it sports inside—and when you first buy this thing, you will probably be burning and re-flashing live installs for your system over and over. I eventually found a multi-OS live install that made it possible to get a feel for every major mobile Linux option without having to go through the rigamarole of opening up the back every time.

The best part about the live CD is that if you enjoy Linux, you can now take the demo for granted. Trying a new OS is as easy as spinning up a VM or flashing a new disc.

But there was a time that you couldn’t. And as a community, Linux solved this problem—and likely set the stage for decades of evolution and growth.

All it takes is the right person being willing to try something new.

--

Find this one an interesting read? Share it with a pal, possibly on a business card CD-ROM!

And thanks again to Masterworks for sponsoring.